King William’s War, also known as the Second Indian War and the First French and Indian War, was an armed conflict between England and France in North America in the 17th century.

WILLIAM of Orange fought his way to take the English crown in the late 17th century in what was later known as The Glorious Revolution. Known as 'King Billy' in Northern Ireland, he is still. Haverhill The Battle of Port Royal (19 May 1690) occurred at Port Royal, the capital of Acadia, during King William's War. A large force of New England provincial militia arrived before Port Royal.

The war was a battle over control of North America, particularly over the fur trade in North America.

Thewar was an extension of the Nine Year’s War in Europe, also known asthe War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg,which was a battle for the English throne.

Who Fought in King William’s War?

- England

- Iroquois Confederacy

- France

- Wabanaki Confederacy

When Did King William’s War Take Place?

KingWilliam’s War was fought between 1688 and 1699.

Where Did King William’s War Take Place?

Thebattles of King William’s War took place in the following locationsin North America:

- Colony of Connecticut

- Colony of New France

- Province of New Hampshire

- Province of New York

What Caused King William’s War?

The Nine Year’s War was essentially a power struggle between the King of France, Louis XIV, and the King of England, William III, after William III overthrew the former King of England, James II, in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and James escaped to France, where he and Louis XIV joined forces to take back the English throne and reinstate Catholic rule.

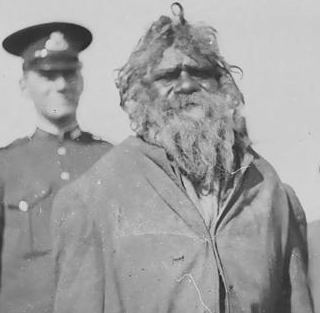

1690 King Billy's On The Wall

TheNine Year’s War began when French forces invaded the Rhineland (whatis now modern day Germany and the Netherlands) in late 1688.

In response, England, the Dutch Republic and the Holy Roman Emporer Leopold formed an anti-French coalition in 1689, known as the League of Augsburg, to combat the French military aggression.

Thefighting between France and England then spilled over into NorthAmerica, where both France and England had colonies and had long beenstruggling for control of the continent.

Accordingto Michael Laramie in his book King William’s War: The Contest forNorth America, there were actually a number of ongoing problems inthe North America colonies at the time that led to the outbreak ofwar:

“King William’s War was actually three conflicts. The first of these was a long-running feud between the Iroqouis Confederacy, New France, and New France’s native allies. Fueled by English guns and money as well as the confederacy’s desire to divert the French fur trade toward their English trading partners in Albany, this conflict had started with the opening pages of the French colony. To the east another conflict would be captured under the banner of King William’s War. The pro-French Wabanaki of Maine, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick had previously fought in the New England. English expansion and French urgings, aided by foolish moves and political blunders on the part of New England, erupted into a second Wabanaki war on the eve of King William’s War. Thus, these two proxy wars fought by the English and the French through their native allies officially became one with news of a declaration of war between France and England in 1689.”

InApril of 1688, St. Castin’s Trading House in Maine was plundered byEnglish Governor Andros, which is believed to be one of the majorevents that kicked off the war, according to the book The Collectionsof the Maine Historical Society:

“Of the several causes assigned for the commencement of the second Indian War, the more immediate one was the plundering of the Baron de St. Castine’s trading-house by Gov. Andros. The governor pretended that it was situated within the limits of the English jurisdiction; this, Castine would not acknowledge. He was a Frenchman, and son-in-law of Madockawando Chief Sachem of the Eastern Indians, and was therefore possessed of an influence, with both the French Missionaries, and the Indians, which he might at any moment exert against the English settlers. By Castine and his party the Indians of Maine were soon induced to take arms against the English” (Maine Historical Society 135).

WhatHappened During King William’s War?

In response to Andros’ raid, the Baron de St. Castin, Jean-Vincent d’Abbadie, and the Wabanaki Confederacy began a military campaign along the border of New England and Acadia (a colony of New France in modern-day Maine and Quebec.)

Thecampaign began on August 13, 1689 when Castin attacked New Dartmouth(Newcastle) and killed a few settlers. A few days later they killedtwo people in Yarmouth, in what became the first battle of KingWilliam’s War. Then in Kennebunk, in the fall of 1688, they killedtwo families.

OnFebruary 13, 1689, King William III and Mary II officially replacedJames II as the rulers of England.

When news of the Glorious Revolution reached New England in March of 1689, talk of an uprising against the Dominion of New England began and, in April, a mob finally rose up in Boston and overthrew the Governor of the Dominion of New England, Sir Edmund Andros.

Then,on May 17, 1689, England officially declared war on France, whichchanged the tone of the conflict in North America, according toHoward H. Peckham in his book The Colonial Wars:

“When news reached the English colonies during the summer of 1689 that Britain had declared war on France, Massachusetts and New York had already exchanged blows with their popish neighbors to the north. Yet these forays had been localized hostilities, like fights between neighboring children, which the parent countries could smooth over. This time, however, the parents were fully committed. The enemy was common on both sides of the Atlantic for both Englishman and Frenchman.” (Peckham 25).

OnJune 27, 1689, Abanaki and Pennacook Indians under the command ofKancamangus and Mesandowit raided Dover, New Hampshire, where theykilled more than 20 people and took 29 captives that they later soldinto slavery in New France.

InAugust of 1689, Castin and Father Louis-Perry Thury led an Abanakiwar party that captured and destroyed the fort at Pemaquid in Acadia.

Alsoin August of 1689, Iroqouis warriors attacked the French settlementat Lachine in Quebec. In response, Governor General Count Frontenacthen attacked the Iroquois village of Ononaga in New York.

Inresponse to the raids in Acadia, Major Benjamin Church led four warparties on a series of expeditions into Acadia.

Thefirst expedition occurred in September of 1689, whenChurch led a war party of 250 soldiers to defend a group of Englishsettlers at Falmouth from the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Wabanakikilled 21 of Church’s soldiers in the conflict, but Church wassuccessful in forcing the natives to retreat.

Inthe winter of 1690, Count Frontenac of New France planned threeexpeditions, one in New York one in New Hampshire and one in Maine,and began attacking English frontier settlements in these colonies,according to Charles Augustus Goodrich in his book A History of theUnited States of America:

“Count Frontenac, a brave and enterprising officer, was now the governor of Canada. Inflamed with the resentment which had kindled in the bosom of his master, Louis XIV, of France, against William, for his treatment of James, he fitted out three expeditions, in the dead of winter, against the American colonies – one against New York, a second against New Hampshire, and a third against the province of Maine. Each of these parties, in the execution of their orders, marked their progress with plunder, fired and death.” (Goodrich 68).

King Billy 1690

Theexpeditions resulted in the Schenectady Massacre in New York onFebruary 8, during which 60 people were killed, the Raid on SalmonFalls in New Hampshire on March 27, during which 34 people werekilled, and the attack on Falmouth in Maine on May 16, during which200 people were killed, most of whom were survivors of the earliermassacre in 1689.

In response to the massacres, SirWilliam Phips retaliated by leading an attack on Port Royal, thecapital of Acadia, on May 9, 1690. Phips captured and destroyed thenewly constructed fort there, forced the French settlers to declaretheir allegiance to the King of England and took control of thecapital.

On May 16, 1690, the Battle of Falmouthtook place in Casco Bay, during which the Wabanaki Confederacy andFrench forces led by Baron St. Castin and Joseph-François Hertel dela Fresnière attacked and captured an English fort there named FortLoyal, killing 200 English settlers in the process.

BenjaminChurch’s second expedition in Acadia occurred in September of 1690when he led 300 troops on a mission to reduce the Indian populationin Acadia. Church and his troops attacked Fort Pejepscot inmodern-day Burnswick and then attacked another settlement known asPurpooduck at Cape Elizabeth in Maine before returning toMassachusetts.

Encouraged by their success at Port Royal, Massachusetts led a two-pronged attack on French Canada in the fall of 1690. Phips led 2,200 Massachusetts troops in an assault on Quebec while Fitz-John Winthrop attacked Montreal with a force of New York and Connecticut militia and Native-American allies. Unfortunately, both attacks failed.

On January 24, 1692, the CandlemasMassacre, also known as the Raid on York, took place when ChiefMadockawando and Father Louis-Perry Thury led 200-300indians on an attack on York, Maine, killing about 100 Englishsettlers and taking another 80 captive.

On June 10, 1692, around 500 French andIndians attacked Wells, Maine but were defeated after a 48-hour-longsiege.

Benjamin Church embarked on his thirdexpedition into Acadia in 1692, when he led 450 troops in variousraids in the Penobscot region.

In the midst of the war, during the spring of 1692, the Salem Witch Trials began in Massachusetts, which many historians believe was partly caused by tension and stress due to King William’s War.

Historian Howard H. Peckham even suggests in his book, The Colonial Wars, that the colonists were naturally gullible and this may have been what led them to accuse each other and also may have been what led them into war with the French in the first place:

“Massachusetts was now distracted by its witchcraft delusion. Inspired by their religious leaders, the less educated readily succumbed to the preposterous hysteria. Innocent if at times eccentric persons were accused of fantastic crimes and influence, and twenty were executed – for their own good, of course. After the terror had run its course and rational minds prevailed again, the presiding judges in several of the cases recanted his action, but the local clergy were unwilling to concede that the devil had not been active in their midst. So credulous a people would readily believe any partial truth about the French” (Peckham 45).

Afterit was all said and done, 19 people were hanged, one person waspressed to death and a handful of people died in jail before thetrials finally ended in 1693.

Meanwhile, the war raged on and, on July 18, 1694, French soldier Claude-Sébastien de Villieu and about 250 Abenakis raided the English settlement of Durham, New Hampshire, killing and capturing around 100 people and burning half the dwellings, including five garrisons, in what later came to be known as the Oyster River Massacre.

On August 15, 1694, a peace treaty wassigned between representatives from the colonies of Connecticut,Massachusetts-Bay, New Jersey and New York and the Iroquois League atAlbany.

In 1696, Castin and Wabanaki warriors returned to Acadia where they fought a naval battle in the Bay of Fundy, raided Pemaquid and then began the Avalon Peninsula Campaign, during which they destroyed almost every English settlement in Newfoundland.

In retaliation, Church’s embarked onhis fourth expedition into Acadia in 1696, when he led his troops inan attack on Fort Nashwaak, which was then the capital of Acadia, andalso raided Chignecto, killing the inhabitants of the settlement inthe process.

The following spring, the French andtheir Indian allies attacked the village of Haverhill in the Provinceof Massachusetts Bay on March 15, 1697.

On September 5, 1697, the Battle of Hudson Bay, one of the war’s major naval battles, took place in Canada when a single French ship defeated three English ships and went on to capture York Factory, a settlement and trading post in Canada.

The last battle of the war, the Battleof Damariscotta, occurred on September 9, 1697 in Maine during which25 indians were killed.

How Did King William’s War End?

TheNine Year’s War ended on October 30, 1697, when the Treaty of Ryswickwas signed.

The treaty stipulated that the borders of New France, New England, and New York remain unchanged but claims to some of the disputed territories were left unresolved, which later led to more unrest and caused the outbreak of Queen Anne’s War in 1702, according to Goodrich:

“By the treaty of Ryswick, it was in general terms agreed, that France and England should mutually restore each other all conquests made during the war. But the rights and pretensions of either monarch to certain places in Hudson’s Bay, & c, were left to be ascertained and determined at some future day, by commissioners. The evil consequences of leaving boundaries thus unsettled were soon perceived. Disputes arose, which, mingling with other differences of still greater importance, led England to declare war against France and Spain, May 4, 1702.” (Goodrich 73).

TheNorth American theatre of the Nine Year’s War, King William’s War,did not end until January 7, 1699, when a peace treaty was signedbetween the Abenaki and the colony of Massachusetts-Bay in Casco Bay,Maine.

Afterthe English and French made peace in 1697, the Iroquois remained atwar with New France until 1701 when the French signed apeace agreement, known as the Great Peace of Montreal, in Montrealbetween New France and the Five Iroquois Nations and more than 35Native nations.

Resentment and border disputes between the English colonists, French colonists and the Native-Americans continued though and eventually resulted in another French and Indian war, known as Queen Anne’s War, in 1702.

How Did King William’s War Affect the Colonies?

According to the New Hampshire Roots website, the war resulted in the death of between 500-600 people in New England and many more were taken captive:

“During this contest as many as sixty attacks had been made on New England settlements by the French and Indians, and between five and six hundred had been slain, not taking into consideration those captured and taken to Canada.”

Sources:

Collections of the Maine Historical Society. Vol. III, Maine Historical Society, 1853.

Goodrich, Charles Augustus. A History of the United States of America. James Cutler & Co, 1832.

Packham, Howard H. The Colonial Wars 1689-1762. University of Chicago Press, 1964.

Drake, Sir Frances. The Border Wars of New England: Commonly Called King William’s and Queen Anne’s Wars. Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1897.

Lossing, Benson John. Harper’s Encyclopedia of United States History from 458 A.D. To 1909. Vol. IX, Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1905.

“Chapter X: Early Indians Wars.” New Hampshire Roots, www.nh-roots.org/hillsborough/goffstown/book/chap10.html

“The Candlemas Massacre and the Salem Witch Trials.” New England Historical Society, www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/candlemas-massacre-salem-witch-trials/

Kences, James. “King William’s War and the Candlemas Raid of January 1692.” Seacoast Online, 10 April. 2018, www.seacoastonline.com/news/20180410/king-williams-war-and-candlemas-raid-of-january-1692

Pin it for later:

| Battle of Port Royal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of King William's War | |||||||

Sir William Phips | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Sir William Phips John March | Louis-Alexandre des Friches de Meneval Pierre Maisonnat dit Baptiste | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 446 provincial soldiers 226 seamen 7 warships 78 cannons[1] | Fewer than 90 soldiers 18 cannons (none mounted)[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | All surrendered | ||||||

The Battle of Port Royal (19 May 1690) occurred at Port Royal, the capital of Acadia, during King William's War. A large force of New England provincial militia arrived before Port Royal. The Governor of Acadia Louis-Alexandre des Friches de Menneval had only 70 soldiers; the unfinished enceinte remained open and its 18 cannon had not been brought into firing positions; 42 young men of Port-Royal were absent. Any resistance therefore appeared useless.[3] Meneval surrendered without resistance not long after the New Englanders arrived. The New Englanders, led by Sir William Phips, after alleging Acadian violations of the terms of surrender, plundered the town and the fort.

After the British sacked Pentagouet, the Wabanaki Confederacy's retaliated with raids along the New England border (See Siege of Pemaquid (1689) and Raid on Salmon Falls) . These attacks were coordinated from Fort Meductic in Acadia. The merchants of Salem and Boston got up a subscription, and in the spring of 1690 the government of Massachusetts organized a campaign led by William Phips against the Acadian settlements.[3]

The aftermath of the surrender of Port Royal was unlike any of the previous military campaigns against Acadia. The violence of the plunder alienated many of the Acadians from the New Englanders, broke their trust, and made future relations with their English-speaking neighbors more difficult.[4] Meneval was replaced by Governor Joseph de Villebon who moved the capital of Acadia to Fort Nashwaak on the Saint John River for defensive purposes, and to better coordinate military attacks on New England with the natives at Meductic Indian Village / Fort Meductic.

Historical context[edit]

The Nine Years' War, begun in 1688 in Europe, widened to include the Kingdom of England in 1689 as part of the alliance against France.[5] Authorities in New France capitalized on turmoil in the English colonies in the aftermath of the 1688 Glorious Revolution to launch raids with their Indian allies against targets on the already tense frontiers of New England and New York. Two raids in early 1690, one against Schenectady, New York and the other on Salmon Falls, New Hampshire, galvanized authorities in the Massachusetts Bay Colony to authorize a retaliatory expedition against French Acadia.[6]

The idea for an expedition against Acadia first arose in the wake of the August 1689 fall of Fort William Henry at Pemaquid (present-day Bristol, Maine) to French and Indian forces.[7] In December 1689 Massachusetts authorized an essentially volunteer expedition against Acadia, and established committees to organize it, but the urgency to deal with it brought more public support after the raids in early 1690. Several prominent colonists were considered to lead it. One of the expedition's major proponents, the merchant John Nelson, was rejected because of his previous trade dealings with the French in Acadia.[6] The command was finally given to Sir William Phips, a Maine native with no military experience who achieved prominence by finding a wrecked treasure ship in the West Indies.[8] (Phips had survived a raid by tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy from Acadia when they destroyed his hometown near Portland, Maine during the First Abenaki War (1676).) On 24 March Phips was commissioned a major general and given command of the expedition.[6]

On 28 April 1690 Phips sailed from Boston with a fleet of five ships, carrying 446 provincial militia. His flagship, the Six Friends, mounted 42 guns, while the Porcupine mounted 16. They were accompanied by the sloop Mary and two ketches. At Mount Desert Island they made a rendezvous with the barqueUnion and another ketch. After investigating French holdings in Penobscot Bay and Passamaquoddy Bay, Phips sailed for Port Royal, arriving near Port Royal on 9 May.[2] Before approaching the town, he made contact with Pierre Melanson dit Laverdure, a bilingual French Huguenot, early the next morning, and ascertained the condition of the town. He then weighed anchor and sailed up to the town.[9]

Surrender[edit]

The French garrison consisted of fewer than 90 soldiers, and the fortifications were in a state of destruction. A military engineer had arrived in October 1689 and had begun razing the fort in order build a new one, over the objections of Governor Louis-Alexandre des Friches de Meneval, and none of its cannons were mounted. Furthermore, the garrison only possessed 19 muskets.[9]

When Phips sent an emissary on 10 May to demand the fort's surrender, Meneval sent the local priest, Louis Petit, to negotiate terms of surrender. The basic terms he and Phips agreed included protection of the persons and personal property of the Acadians, and preservation of their right to Catholic worship. Phips refused to put the terms in writing, but they were reconfirmed by multiple witnesses when Governor Meneval came to the Six Friends the next day.[10]

Aftermath[edit]

What occurred after the surrender, and the motives for it, has been a subject of historical debate,[10] because French and English sources disagree on a number of points. The terms of the surrendered were breached, and the English militia plundered not only the fort but the town as well, and they desecrated the fort's chapel. Private property was taken and livestock killed.[11]

By English accounts, French soldiers and residents were seen removing stores from the fort (which would normally go to the victor as spoils of war) while the surrender negotiations were taking place. When Phips was made aware of this, he flew into a rage, declared the agreement void, and permitted the plunder to take place.[11]

French accounts tell a slightly different story. Governor Meneval supposedly did not leave detailed orders when he went to parley with Phips, and some of the garrison's soldiers began drinking. They then broke into merchant stores belonging to one of Meneval's political opponents, Francois-marie Perrot, and removed his goods from the storehouse. It is unclear whether they removed goods belonging to either other merchants or to the government. Since only the 'King's Stores' were supposedly part of the surrender agreement, Phips biographers Baker and Reid note that there is 'room for doubt whether the agreed terms would thereby have been breached.'[11]

Meneval and Petit, when they reported the events, claimed that Phips, unhappy with the condition of the fort and the size of the garrison that had surrendered, used the action of the French soldiers as an excuse to terminate the agreement.[12] However, the fact that Phips had met with Laverdure prior to approaching Port Royal, and had a presumably reliable assessment of the conditions in the town, renders this explanation unlikely.[9]

Phips' biographers posit that it is more likely that Phips needed to have as much plunder as possible. Spoils from the expedition were expected to pay its costs, and Phips made a verbal surrender agreement as 'a convenience that could be disposed with' once the surrender had been given.[12]

Consequences[edit]

Phips also ordered the Acadian peasantry to swear an oath of allegiance to William III and Mary II of England. Phips then determined to install a new government; he organized a provisional government by personally selecting French Acadian leaders to form a council. The council's government did not last long. Joseph Robineau de Villebon, one of Meneval's assistants, returned to Port Royal from France in June, and reestablished French authority. He moved the capital to Fort Nashwaak on the Saint John River for defensive purposes, and to better coordinate military activities with the Abenaki. Port Royal was subjected to a pirate raid not long after the Phips expedition left. The pirates captured the ship that delivered Villebon, destroyed homes and cattle, and allegedly killed some of the inhabitants.[13]

Phips detached Cyprian Southack, commander of the Porcupine, with orders to raid a French fishing port on the Atlantic coast of the Acadian peninsula. Southack went on to conquer Fort St. Louis in the Battle of Chedabucto. Phips returned to Boston, where he was chosen to lead a larger expedition against Quebec later that year, which was a disastrous failure. Phips retained his popularity in New England, and was appointed governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay in 1692 by King William. He continued to be involved in the war until he was recalled in late 1694.

The expedition marked the climax of a period of steadily worsening relations between New Englanders and the French imperial authorities, and reconfigured relations between New England and Acadia.[14] Trade was affected, since those who wanted profitable trade with the Mi'kmaq and Acadians, led by John Nelson, failed to gain control of the expedition.[6][15]

The following year, after the English lost a naval battle off St. John, Villebon tried unsuccessfully to negotiate the freedom of 60 French prisoners taken in the siege.

References[edit]

- ^Griffiths (2005), pp. 150–151.

- ^ abBaker and Reid, p. 87

- ^ abBaudry, René (1979) [1969]. 'Des Friches de Menneval, Louis-Alexandre'. In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- ^Plank, p. 32

- ^Plank, pp. 10–11

- ^ abcdBaker and Reid, p. 84

- ^Baker and Reid, p. 83

- ^Plank, pp. 14–15

- ^ abcBaker and Reid, p. 88

- ^ abGriffiths (2005), p. 151.

- ^ abcBaker and Reid, p. 89

- ^ abBaker and Reid, p. 90

- ^Calnek, p. 39

- ^Plank, p. 10

- ^Plank, p. 11

Sources[edit]

Primary

Secondary

- Baker, Emerson W; Reid, John G (1998). The New England Knight: Sir William Phips, 1651–1695. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN978-0-8020-0925-8. OCLC222435560.

- Calnek, William (1897). History of the County of Annapolis. William Briggs. p. 39. OCLC3227732.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN978-0-393-05135-3. OCLC217980421.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN978-0-7735-2699-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lounsberry, Alice (1941). Sir William Phips. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC3040370.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN978-0-8122-1869-5. OCLC424128960.

Further reading[edit]

- Parks Canada, Port Royal National Historic Site brochure, undated (2001 ?).

- A Journal of The Proceedings In The Late Expedition To Port-Royal, On Board Their Majesties Ship, The Six Friends, The Honourable Sr. William Phipps Knight, Commander In Chief &c. A True Copy, Attested By Joshua Natstock Clerk.

External links[edit]

Coordinates: 44°42′40″N65°36′36″W / 44.71111°N 65.61000°W